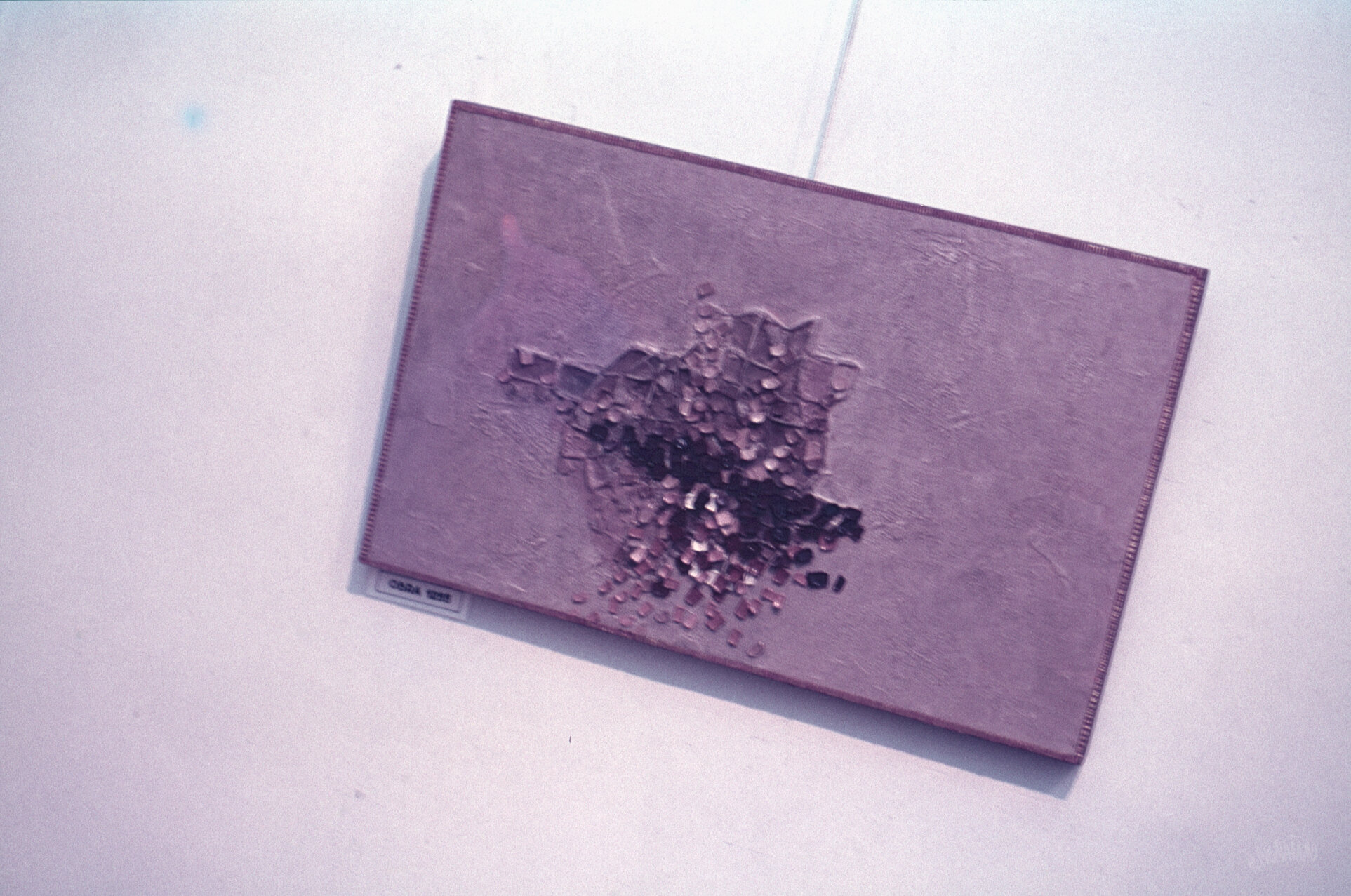

Roberto Pignataro at his 1970 exhibition at Galería Lirolay

If I had to single out a moment in Roberto Pignataro’s career that best captures his transcendence as an artist, it would be his 1970 exhibition at Galería Lirolay.

This show stood out for several reasons: above all, the originality of the abstractions he unveiled; but also a memorable scene in which César Magrini, a respected art critic of the time, was left speechless before them; and, lastly, the complicated backdrop of his overlapping exhibition at the Miami MoMA.

This article revisits that show, the context in which it took place, and Magrini’s remarkable response to it.

•••

1. The Path to Three-Dimensionality

Before getting into the story, I want to take a moment to focus on a more technical aspect — Pignataro’s artistic development throughout the 1960s and the creative strategies that brought him to this point. If you’d prefer to skip the technical analysis, feel free to jump ahead to Section 4: “An Art Critic Enters the Showroom,” where the story itself begins.

—

From early on in his career, Pignataro recognized that abstraction—with its elusive language and resistance to fixed interpretation—could at times feel intimidating.

He addressed this challenge by investing heavily in visually striking compositional techniques, understanding that appealing to the eye was essential to draw the viewer into the experience of abstraction.

Observing his artistic progression between 1961 and 1969, it becomes clear how deliberately he pursued this strategy. His techniques grew more visually arresting with each exhibition—evolving from heavy brushstrokes, textured impastos, and multilayered collages of the early 1960s to the increasingly sculptural mixed-media and assemblage works from the mid-1960s onward.

To illustrate this progression, below are close-ups from selected works exhibited from this period (click to enlarge).

As this evolution shows, three-dimensionality emerged as Pignataro’s chosen device for engagement—a visual subterfuge that invites proximity while quietly luring the viewer’s eye into the deeper, more demanding layers of his abstractions.

With this context in mind, let’s now address the novel artistic strategy he developed for his 1970 show.

•••

2. A New Visual Language Emerges

Up until 1969, everyday objects were the primary means by which Pignataro infused three-dimensionality into his work. Sliced corks, staples, matches, sisal thread, bottle lids, punched tape, paper, and rubber bands frequently appeared in his assemblages, forming pronounced textures, raised grids, topographic surfaces, and protruding motifs.

Close-up of № 1012 (1967), Roberto Pignataro. Featuring cork slices and oil paint tube caps.

For his 1970 show, however, he sought a new approach. Determined to move beyond the familiar vocabulary of assemblage, Pignataro set out to explore three-dimensionality through compositional methods that had not been attempted before.

To this end, he returned to a technique he had quietly introduced in 1968 at Galería Lirolay: the controlled application of small oil paint squeezes directly onto the canvas, producing scattered raised dots that added visual rhythm and a subtle tactile presence to the work.

This curious technique resurfaced in his subsequent 1969 exhibition, appearing in two assemblages. In the first one (below, left), the dotted deposits lie loosely scattered across pale areas of the surface, particularly around the white impastos and bluish cork slices. In the second (below, right), the dots cluster more densely, forming intricate groupings across the red field.

Comparing the two pieces, it becomes clear that № 1168 marks a decisive shift in the technique. Here, the raised dots no longer sit quietly as supporting elements within a larger assemblage—they assert themselves as the foundation of a new visual logic.

This is the moment when Pignataro turned what originated in 1968 as a modest device into a full compositional strategy of its own, opening entirely new possibilities for oil paint as a medium.

Full view of artwork “№ 1168”

As he composed the works for his upcoming 1970 show, he expanded this technique to new extremes. No longer confined to a supporting role, the extruded paint bits now swept across entire surfaces—taking on diverse shapes such as circles, triangles, squares, ovals, even crescent moons—and forming intricate, multilayered structures.

The slideshow below shows the result: ten abstractions entirely developed in this new visual language.

•••

3. Beyond Category

Like most artists, Roberto Pignataro’s path into modern art was shaped by earlier movements — in his case, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, ancient Japanese art, and others. Although his work always carried a distinct identity, traces of these influences remained visible up to this point.

What emerged in his 1970 show, however, was different. Existing art categories were no longer sufficient to fully describe what he unveiled. His new work stepped so far beyond recognizable precedents that, even today, trained and art-literate viewers, I have noticed, struggle to articulate what stands before them.

And even beyond questions of categorization, it’s hard to overstate how insane this technique really is, specially when seen up close. The artistic novelty alone is remarkable—but the technical gamble is borderline reckless. Given how difficult oil is to control at this level; you might spend an entire week shaping these structures only to watch it all collapse from a slip of the hand, a bad call, or simply because the composition didn’t evolve as you hoped. And there’s no undo button—a mistake at this stage means tearing it all down and starting over.

Yet he pulled it off, and with a level of material detail and color nuance that defies what should be possible.

Close-up of "№ 1227" (1969), by Roberto Pignataro.

Close-up of "№ 1220" (1969), by Roberto Pignataro.

•••

4. An Art Critic Enters the Showroom

César Magrini (1929–2012) — Argentine writer, journalist, and art critic.

With all the pieces now finished, Roberto Pignataro’s 1970 show at Galería Lirolay was finally inaugurated on Monday, September 28.

He typically did not remain present during his exhibitions. Unlike many artists, he did not enjoy the limelight. Furthermore, he believed an artist’s presence could interfere with the viewer’s unmediated encounter with the work — an experience he wanted to unfold freely, without any suggestion or influence.

This show was no exception. By the time a visitor stepped into the gallery, Pignataro was almost certainly at his desk at the Central Bank of Argentina, immersed in his daily number-crunching routines, far from the space where his abstractions silently hung.

One of those visitors was César Magrini — a leading Argentine writer, journalist, and art critic deeply involved in the country’s cultural scene of this period.

It was in this setting — a show in progress, with Pignataro absent by design — that Magrini walked into the gallery and encountered the new works for the first time.

Interior view of Galería Lirolay, c. September 1970, during Pignataro’s exhibition.

Artwork visible in the back room is by Blanca Medda, another artist showing simultaneously at the gallery.

Pignataro maintained a warm relationship with Galería Lirolay’s owners, Mario and Paulette Fano. Though he avoided being present during opening hours, he often stopped by in the evenings to hear how the day had unfolded. Paulette, who usually managed the gallery floor, would recount who had visited, whether anyone notable had come through, and how viewers had responded.

That day, she told him that César Magrini had come in — and had spent more than thirty minutes viewing the show, moving slowly through the room, returning to the works again and again. He said almost nothing; he simply looked stunned, absorbing the pieces in silence, occasionally taking notes, before eventually stepping back out onto the street.

César Magrini, “Aprendiz de Hechicero,”

El Cronista Comercial, no. 20.590, September 1970, “Galerías” section.

It was only the next day that his reaction found language when he published a review in El Cronista Comercial — one of Argentina’s leading newspapers — putting into words the impressions this show had left on him.

In the next section, I will walk through Magrini’s review, excerpt by excerpt, tracing how he responded to the work, what elements compelled his attention, and how his language engages with a visual vocabulary that had not yet found a place in the Argentine art landscape.

Before we jump into it, here is a full transcript of Magrini’s article, both in Spanish and English.

•••

5. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

If you’re wondering about this title, it’s the one Magrini chose for his published review. I must confess: when I first read it, I twisted myself into knots trying to understand what connection he might have seen between Goethe’s poem and Pignataro’s show. Eventually, I realized it wasn’t that complicated — it was less a literary reference than a whimsical metaphor, a bit of wordplay meant to capture his enchantment with the exhibition.

Now, with the title context in place, let’s turn to the article:

“At Lirolay, we’ve just seen a tightly arranged exhibition — small in physical space yet expansive in what it held — of works by Roberto Pignataro.

To define it is extremely difficult: like an illuminated child, he has chosen for his compositions the most unusual materials — fragments of glass in various colors; the purest and most pliable magic enclosed within a single chromatic range that nevertheless, by its very vitality, is capable of producing all tones; tiny pieces of (perhaps) ceramic, which he combines like fantastic fleurs-de-lis, like variegated and mysterious fruits — the reign of the finest charm, of the most total and contagious suggestion.”

What immediately stands out in this first excerpt is his struggle to describe what he was seeing. Also notable is his description of the technique, as he misinterpreted the sculpted oil-paint forms as fragments of glass and ceramic. Whether this was an honest mistake or a touch of creative license, it underscores just how unfamiliar this material language was at the time.

“Pignataro, who seems by nature elusive and withdrawn (the small card announcing the exhibition says simply, “Roberto Pignataro in recent paintings,” and I recall an excellent previous show of his), has now turned — with astonishing results — to mastering a material that in other hands would be foreign to painting and to art, and that can only approximately be defined as “assemblage.””

This passage is particularly important. While Magrini continues to grapple with how to classify the work, he also recognizes Pignataro as an artist working entirely on his own terms — in full command of his creative process and far removed form the shadow of artistic influences.

Interestingly, Magrini also notes Pignataro’s elusiveness, echoing what I discussed earlier about his deliberate absence. This observation — whether intentional or not — underscores Pignataro’s conviction that distance between artist and viewer is essential. In other words, had he been present when Magrini visited, the “magic” of his encounter with the artwork might have been diluted by conversation, explanation, or even the faintest hint of authorial intent.

“Of course, he does not stop there; but his character — which can be guessed or intuited from what’s on display, and in the fact that he has not titled his works, only mere numbers (a sign, this, of a sincere intellectual rigor, and one that also helps to situate him) — flourishes widely in his pictures. Yes, pictures — because they immediately awaken in the viewer sensations of the most refined beauty, and on a level of incorruptible honesty.”

Here, Magrini astutely reads Pignataro’s refusal to use descriptive titles not as avoidance but as discipline. By withholding verbal language, he ensures that meaning arises from the encounter itself, rather than from the artist’s direction — a stance Magrini implicitly affirms in his own response.

Magrini then goes on to discuss each piece individually. His comments be read in the transcripts linked above, but in essence his language moves between close observation and poetic metaphor — naming colors and textures, then drifting into images of childhood, fairy tales, and hidden worlds. His response is sensorial rather than analytical, meeting the works through imagination and astonishment rather than technical classification — once again highlighting the magical nature of his experience with the work.

“Someone deep and profoundly original, with a language of his own — lofty, poetic. Someone whose works one ought to see more often, because they rescue us from so much monotony, so much flatness, so much painful poverty as that which daily besieges us.”

For a critic who spent his days moving through exhibitions, Magrini’s closing remarks are quite eye-opening — as much a tribute to this show as they are a scathing indictment of the broader Buenos Aires art scene of late 1970. He pulls no punches, casting Pignataro’s work as a rare moment of clarity amid the creative stagnation he saw everywhere else.

To close this section, it’s worth noting that Magrini and Pignataro had not yet met in person, even though Magrini mentions having seen an earlier show. They would cross paths only briefly in later years. This review, then, reflects a genuine response — a moment of true awe, entirely uncolored by personal connection or obligation.

•••

6. Triumph and Turmoil

For Roberto Pignataro, this moment in his career offered many reason to celebrate: a breakthrough artistic proposition, Magrini’s emphatic acknowledgment, and — on the personal side — the joy of having recently become a father to his first child.

However, there is a side to this story I have not yet introduced — While this show was unfolding, he was carrying the weight of a long-brewing fiasco that had been grinding him down for months. Allow me to elaborate:

A year earlier, in September 1969, he had begun preparing for his first international exhibition in Miami. The show was scheduled to open in May 1970 at the Miami MoMA — a milestone by any measure. But a devastating shipping incident derailed everything. The artwork disappeared in transit, triggering an international dispute with legal and financial consequences, a rupture with the museum, and months of escalating uncertainty.

At the time of his Galería Lirolay show, the paintings for his Miami exhibition were still missing. He was actively trying to resolve the incident — shuttling between offices, filing claims, and chasing answers through a maze of shipping agents, port authorities, insurance firms, consulates, lawyers, customs officials, and the museum itself — an ordeal that was costing him a fortune in money and time, and with no clear resolution in sight.

All of this while, he was holding down his full-time job at the Central Bank and caring for a newborn at home.

I have written extensively about this episode in my article “The Miami MoMA Exhibition,” so I won’t revisit the particulars here. But I felt it was important to share this additional context. This period was a true balancing act for Pignataro, trying to savor a moment of artistic triumph while quietly managing an intensely stressful crisis in the background.

•••

7. Final Thoughts

There are two key reasons why I’m able to reconstruct this story today, fifty-five years after it happened. First, because my father had a habit of documenting his shows, but most importantly because he was fortunate enough that Magrini decided to step into Lirolay that day, providing us with a priceless first-hand account of his experience.

But I often regret how many independent artists and exhibitions from this transformative period in Argentine art — like this very one — have been lost to time, simply because a critic didn’t show up, they weren’t properly documented, or their records simply didn’t survive the artist.

This historical loss becomes painfully evident, for instance, whenever I try researching the artists who once shared exhibition space with my father. Most of the time, I find nothing of substance. Occasionally, a name or exhibition listing might surface on an obscure archival site like the Archivo IIAC, but rarely enough detail to understand who the artist truly was, let alone visual records of their exhibitions.

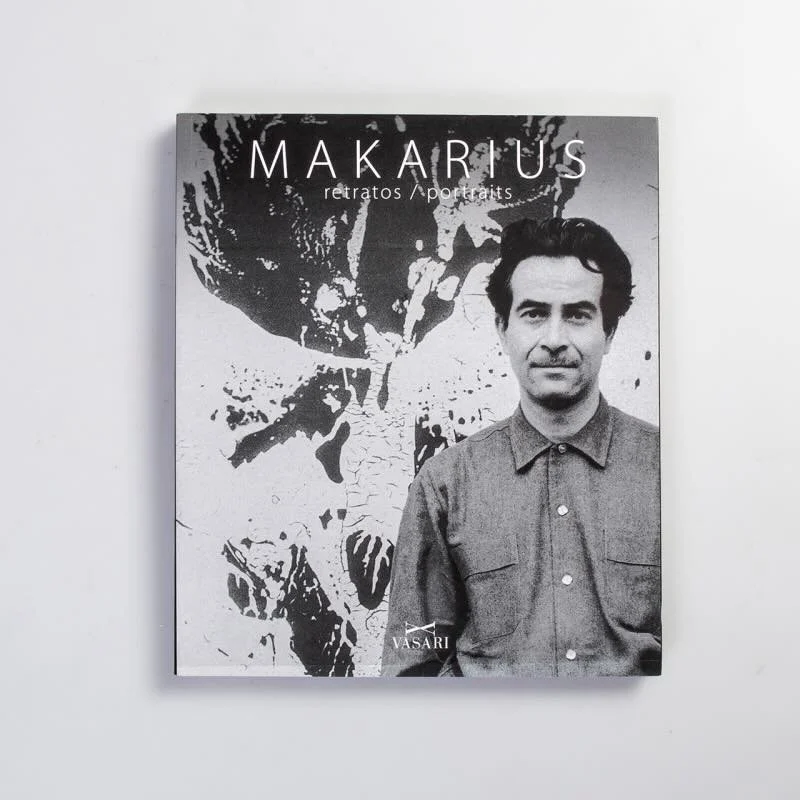

To further illustrate this problem, allow me to turn to ‘Retratos’, a book by Sameer Makarius.

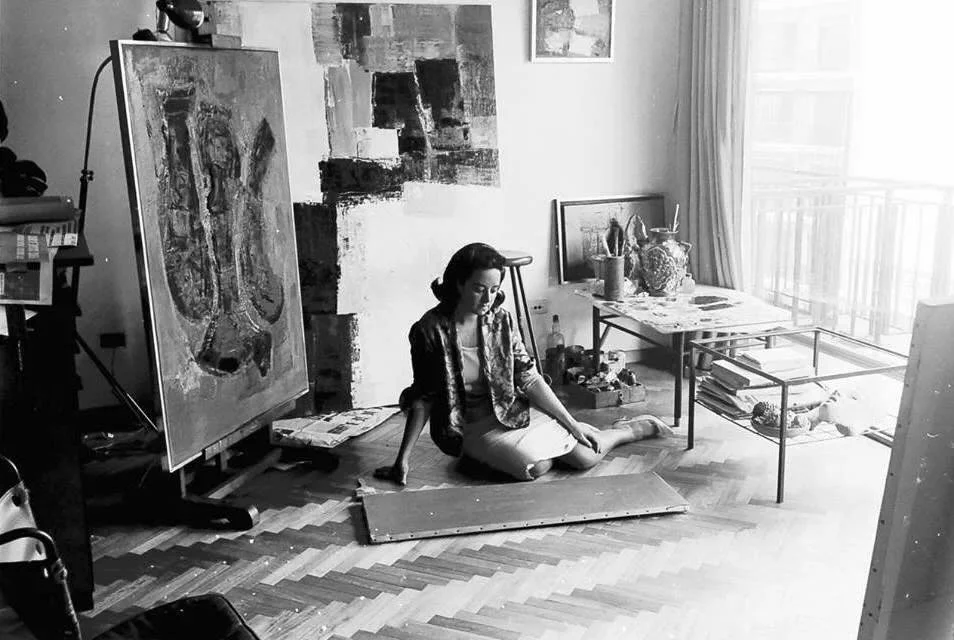

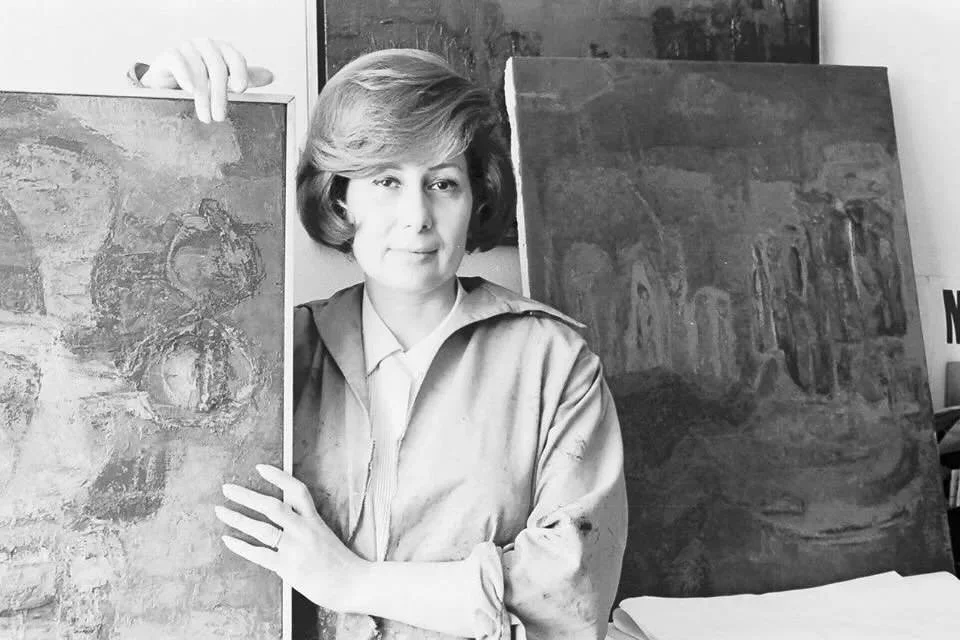

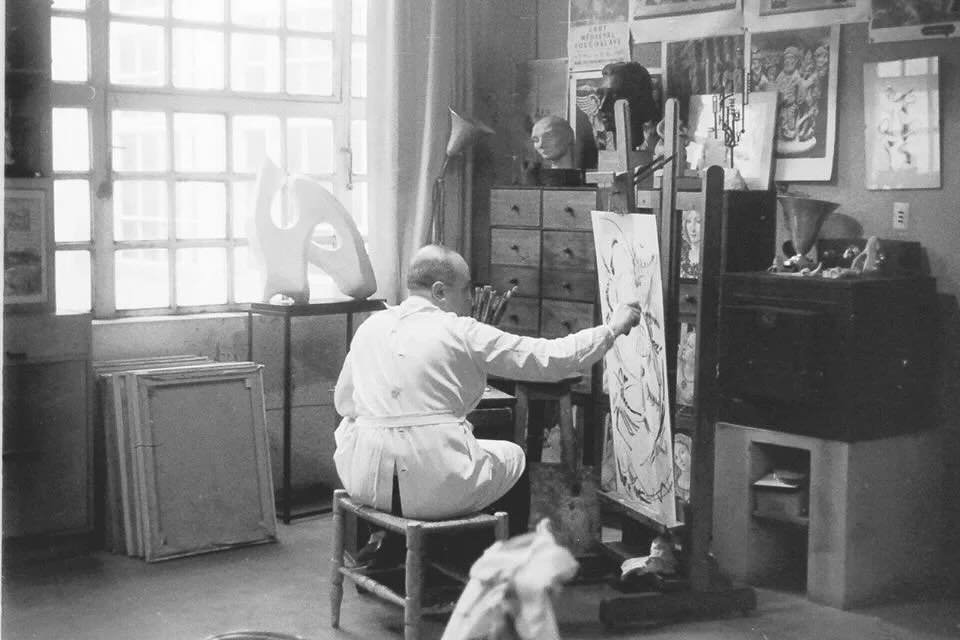

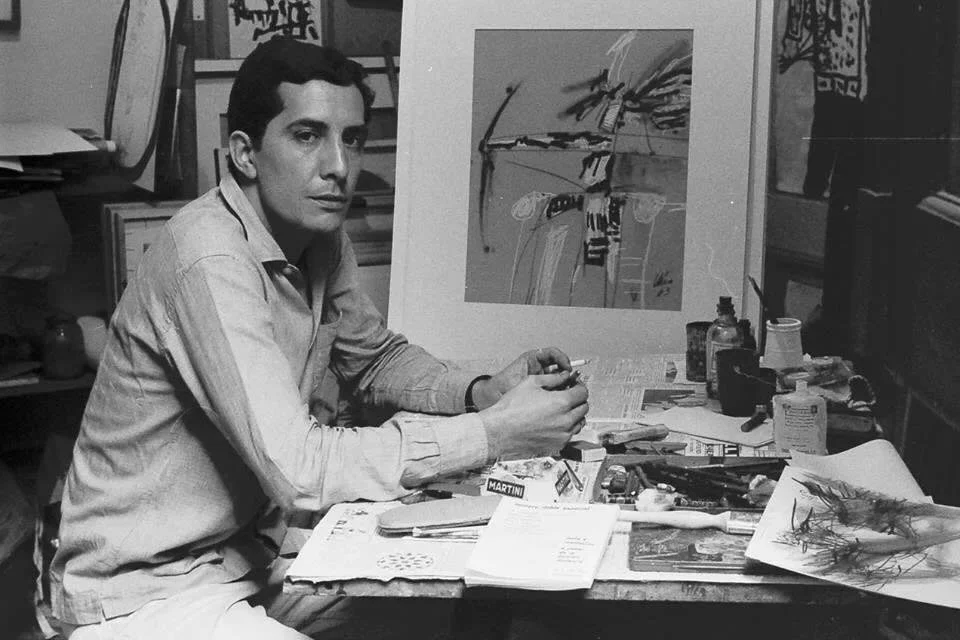

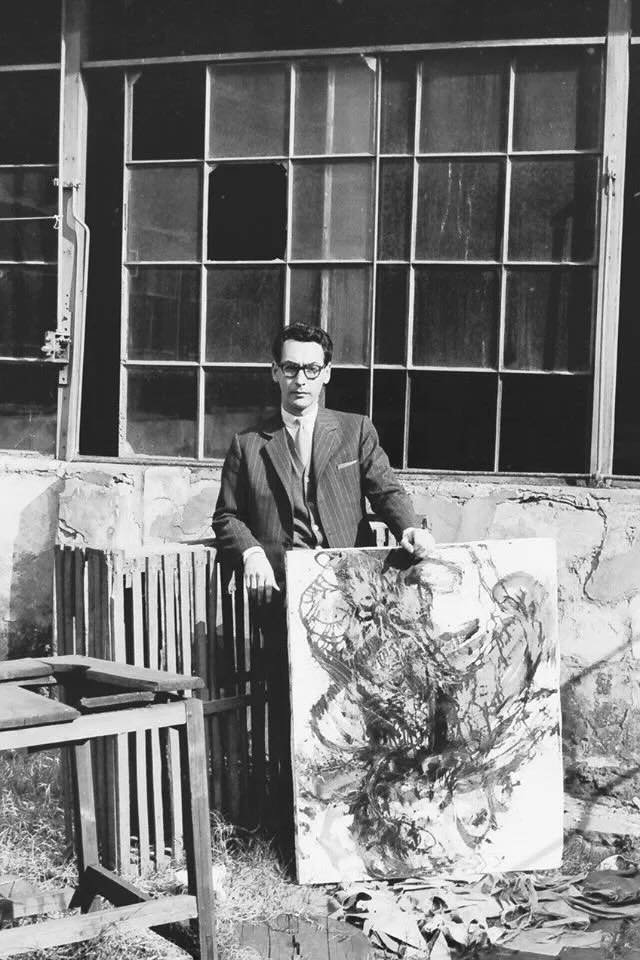

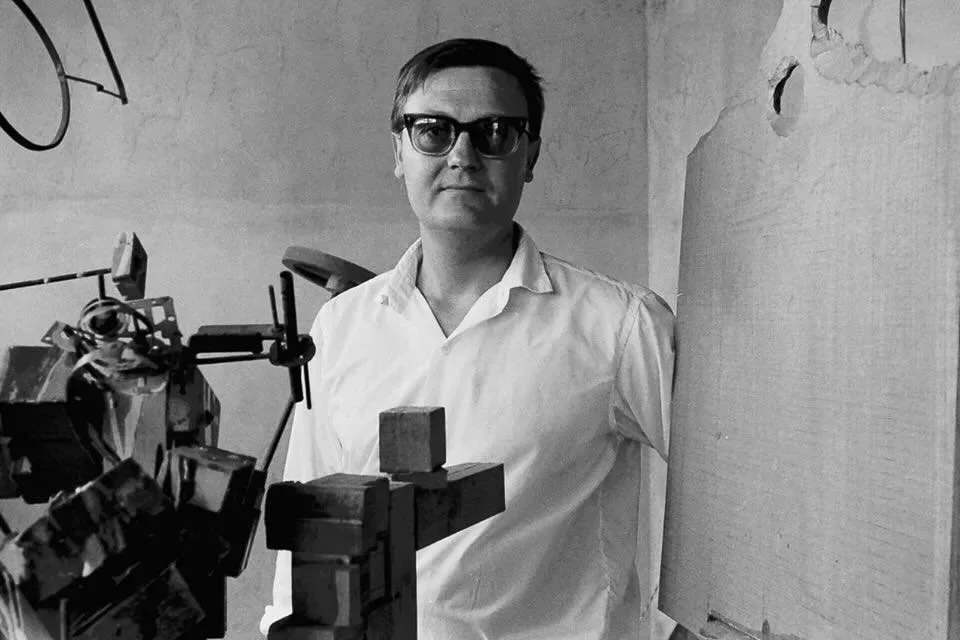

‘Retratos’ is nothing short of a cultural treasure. It features an extremely rare photographic record of Argentine artists in their homes and studios between 1957 and 1967. The gallery below shows just a few sample photographs from this vast collection (the full archive can be found on his son Kareem Makarius’s Facebook page, where he has done an extraordinary job preserving and sharing this legacy.)

Once you see these photographs, it’s impossible not to wonder — who were they? Can we find more information of their exhibitions, their work, their lives, what drove them, what they left behind?

And that’s when the gaps become painfully real — because try as you might, it’s nearly impossible to gather enough to reconstruct these stories in any substantial way.

Yes, much has been documented about the more visible figures of the time, particularly those associated with the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella — Marta Minujín, Luis Felipe “Yuyo” Noé, Kenneth Kemble, and a few others. But these artists did not rise to prominence in isolation; they were part of a much broader generation of talented creators who, unlike them, were barely touched by the spotlight — not because their work lacked merit, but because they weren’t media-savvy enough, well-connected enough, or simply didn’t fit the tastes of the cultural gatekeepers who shaped that era.

This is why these rare accounts matter — whether through Magrini’s words, Makarius’s lens, or Pignataro’s records. They remind us — and challenge historians — to look beyond the established canon, to rediscover the vast constellation of artists and stories that official narratives left behind, still waiting to be seen.

•••