In 1972, Argentine informalist artist Roberto Pignataro self-published his second artistic book entitled, “En Slides Color.” This time, it was a pocket-sized album containing sixteen 35mm slides of “projectable” abstract collages. What’s the story behind this peculiar art project?

•••

Introduction

1965 Art Exhibition by Roberto Pignataro at Galería J. Peuser, Buenos Aires, Argentina

While Pignataro loved and much preferred the art gallery format for showcasing his work, he also recognized its limitations: short-lived events with limited reach and unpredictable attendance.

Creating artistic books offered a practical way to address some of these issues. Unlike exhibitions, books were less ephemeral, easily reproducible, and more accessible to wider audiences through bookstores, libraries, mailing campaigns, and other distribution channels.

Building on this approach, he began self-publishing as a way to promote his art beyond the confines of gallery spaces—particularly to museums and universities in the United States and abroad.

En Slides Color, the focus of this article, represent his second attempt at this strategy—though with one notable peculiarity: unlike his other publications, it consisted entirely of 35mm slides, meant not just to be viewed, but projected.

This article explores the various phases of its production, including its promotional efforts, the historical context in which it emerged, and the art world’s reaction to it.

•••

The Inspiration

Roberto Pignataro at the beach in Chapadmalal, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Circa 1969

The idea of creating “projectable” art on 35mm slides originates not in small part from Pignataro’s enthusiasm for macro photography.

He’d been photographing close-ups of nature, particularly coastal life, since the mid 1960s.

It was a hobby he primarily indulged in during summer vacations on the beaches of Chapadmalal, a town on the southern coast of Buenos Aires.

He was fascinated with the unique characteristics of macro photography; how it provided a more intimate understanding of the subject, and the new realm of textures, patterns and behaviors it revealed to the human eye.

▼ 1968-1969. Slides of coastal life captured by Roberto Pignataro on the beaches of Chapadmalal, Buenos Aires.

After years of experimenting with this medium, it was only natural for aspects of that experience to filter into his artistic practice. This evolution, of course, was made possible by the increasingly accessible slideshow technology of the time—such as backlit viewers and tabletop projectors—which allowed Pignataro’s private observations to evolve not only into a new artistic concept, but one that could be shared.

En Slides Color marks this moment—when art and technology come together, combining abstraction with the immersiveness of macro photography and the versatility of 35mm color slides, not only to create a novel artistic form but also to support a new and original strategy for reaching wider audiences.

•••

The Art Production

To achieve the immersive qualities of macro photography in his artwork, Pignataro needed to create compositions that were not only small enough to fit under a macro lens but also adaptable to the 35mm color slide format. For this, he chose a technique he was very familiar with: paper collage.

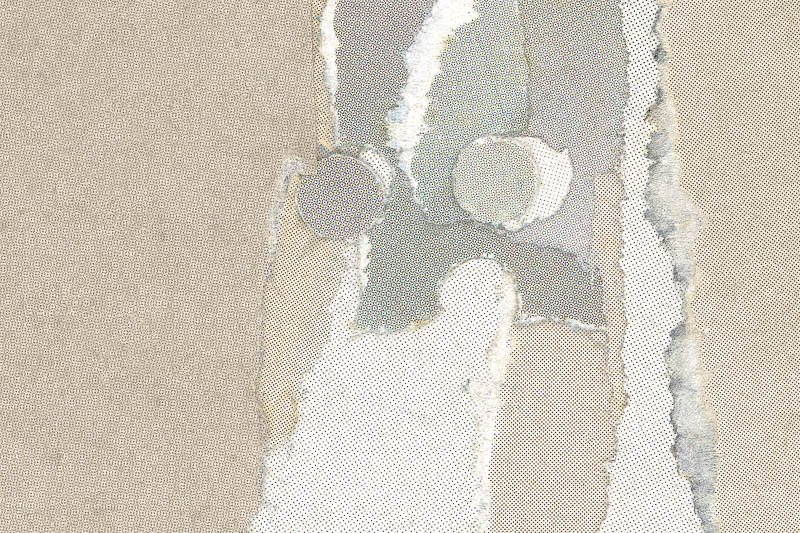

The production of the master artwork began in September 1971. Pignataro started by creating three base collages with torn pieces of paper from various magazines, arranging them into colorful but rather chaotic compositions. He then refined the final product by punching holes in the paper, using both the circular remnants and the resulting negative spaces to better define shapes and develop motifs.

Upon completing the base collages, Pignataro scanned the areas with the most artistic potential using his macro lens and captured them on film. For this process, he employed an Asahi Pentax Spotmatic 35mm SLR camera and Fujichrome R100 film.

•••

The Slides

The slideshow below showcases the final sixteen selections for the book.

It’s important to note that the original slides have color-shifted over time, a common issue with photographic film. As a result, I chose to recapture the master collages using modern scanning technology. This allows the artwork to be appreciated in its full color glory, as Pignataro intended in 1972.

▼ Click to enlarge images

▲ The sixteen collages included in “En Slides Color” (1972)

•••

A Self-Promotional Campaign

▲ “En Slides Color”, front cover. Size: 6.5” x 5”, or 16.5 x 12.3 cm.

With the production of "En Slides Color" complete, Pignataro turned his attention to producing the book and launching his promotional campaign.

Altogether, he had a total of 315 copies printed, marking the first and only edition of the book.

▲ “En Slides Color”, index and first slide sheet.

According to his records, the mailing campaign was directed at art-related institutions and personalities across a diverse range of countries, including Argentina, the United States, Spain, Japan, Canada, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, Israel, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and Paraguay.

Amongst some notable institutions were:

Solomon Guggenheim Museum (NY, USA)

Museum of Modern Art (NY, USA)

Arts Magazine (USA)

Fogg Museum of Art (Harvard University, USA)

Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art (Japan)

Centre Georges Pompidou (France)

Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo (Madrid, Spain)

Museo de Arte Moderno (Argentina)

Miami MoMA (USA)

The Arizona University (USA)

Ecoles D’Art de Genève (Switzerland)

Palacio de Bellas Artes (Mexico)

A page from the list of recipients

Amongst some notable personalities were:

Jorge Romero Brest (AR)

Marta Grinberg (AR)

Pérez Celis (AR)

Paulette & Mario Fano (AR)

Cesar Magrini (AR)

Rafael Squirru (AR)

Guillermo Whitelow (AR)

Ignacio Pirovano (AR)

Jacques Lassaigne (France)

Norman A. Geske (USA)

Hernández Rosselot (AR)

➔ View the full list of recipients

•••

Historical Context

To better understand Pignataro’s motivations for this self-promotional effort, allow me to introduce an excerpt from an interview between Rafael Squirru and Nelly O’Brien de Lacy (1). In their discussion, they address the challenging circumstances faced by Argentine artists in the 1960s and 1970s who sought to establish an international presence.

Rafael Squirru: Is it easy for a South American artist to reach recognition outside of his/her continent?

Nelly O’Brien de Lacy: No, it is not. Of course, I am referring to Argentina, where I live. First of all, we are here at the bottom of the globe and nobody knows very much about us; secondly, not enough was done to promote Argentine art. Really good artists are known only locally and their presentation abroad, without due promotion, would be useless. All art manipulations are in the hands of art dealers; big money can be earned only by a work of art that matches the sophisticated cosmopolitan currents. Unclassified artists have little chance to be successful if they do not have enough money to finance their travel and expenses involved in an exhibition, and not many serious artists possess such financial means. To be "projected" and recognized in important art centers is a very difficult affair and only a few achieve it. In spite of these difficulties and a somber prognosis, art flourishes in South America. It is very original and less directed by trends.

In this context, Pignataro’s concept of “mailable art” becomes even more relevant. As an “unclassified artist,” this approach enabled him to gain international exposure for his work while sidestepping the demands of art dealers, the whims of artistic trends, and the high costs of international exhibitions.

•••

International Reception

With every book he shipped, Pignataro included a cover letter outlining his intentions. He emphasized that the primary goal of the book was to introduce the recipient to his work and hoped they would retain it as a reference for contemporary South American art.

Fortunately, Pignataro preserved all the response letters from recipients, which allows us to gain valuable insights into their reactions and perceptions of his work.

Most recipients understood the premise well, welcoming the idea and graciously agreeing to incorporate the book to their collections. Below are some examples of such acceptance letters (click to enlarge):

Others, however, misunderstood the book’s intent. Perhaps due to lack of clarity in the translations, or even in the statement itself, they assumed Pignataro was either seeking exhibition opportunities or attempting to sell his art, leading them to decline the book.

Below are some examples of declining letters (click to enlarge):

Local Reception

As of this writing, there are no documented responses from Argentine recipients, whether people or institutions. However, it is documented that Pignataro personally delivered copies of the book to many of these recipients. Therefore, any comments or critiques to the book most likely occurred during these individual conversations.

Should any relevant documentation become available in the future, it will be promptly added to this section.

•••

Final Thoughts

In this article, we have explored how Roberto Pignataro produced his booklet En Slides Color and used it as a novel strategy to expand awareness of his work, both locally and internationally

However, this project was neither easy nor inexpensive; it required a substantial investment of personal time, money, and other resources. Thus, one may reasonably ask: was it worth it?

The answer is absolutely yes. En Slides Color was, above all, a highly enjoyable endeavor for Pignataro. It challenged him both artistically and entrepreneurially, pushing him to create art in an uncharted new format while exploring innovative ways to reach audiences.

As the reply letters attest, the book was generally well received, garnering numerous positive comments and acceptance from prestigious entities from around the world. Even in the letters where the book was declined, its quality was often praised.

The fact that En Slides Color was able to generate positive reactions from audiences in such culturally diverse countries like Japan, Colombia, and the United States brought Pignataro a great sense of accomplishment.

The originality of this project cannot be understated. En Slides Color was not merely a book of images—it was a deliberate fusion of artistic expression and emerging media, embracing the mechanics of projection and reproduction to reimagine how abstract art could travel and be experienced.

As for the current state of the booklets: every now and then I Google 'En Slides Color' to see what comes up. To my surprise, it occasionally appears on sites like AbeBooks and Amazon, likely having migrated from its original owners to other entities. Each time I see a copy online, I am fascinated by the thought of whose hands it has passed through over the past 50 years.

I often wonder whether the institutional recipient still maintain their copies, such as the Fogg Art Museum, the Solomon Guggenheim Museum or the Frick Art Reference Library. If they do, the booklet may one day achieve another significant goal: ensuring that Pignataro’s work continues to project his artistic ideas beyond his lifetime.

Hopefully, En Slides Color will eventually emerge from its archival resting places, shedding light into Pignataro’s fascinating artistic journey and the brilliant period in South American art in which he existed.