If I had to single out a moment in Roberto Pignataro’s career that best captures his transcendence as an artist, it would be his 1970 exhibition at Galería Lirolay.

This show stood out for several reasons: above all, the originality of the abstractions he unveiled; but also a memorable scene in which César Magrini, a respected art critic of the time, was left speechless before them; and, lastly, the complicated backdrop of his overlapping exhibition at the Miami MoMA.

This article revisits that show, the context in which it took place, and Magrini’s remarkable response to it.

However, before getting into the story, I want to take a moment to focus on a more technical aspect: the trajectory of Pignataro’s artistic development starting in the early 1960s, and the creative strategies that brought him to this point.

•••

The Path to Three-Dimensionality

From early on in his career, Pignataro recognized that abstraction—with its elusive language and resistance to fixed interpretation—could at times feel intimidating to the viewer. He addressed this challenge by investing heavily in visually striking compositional techniques, understanding that appealing to the eye was essential to ensuring the experience of abstraction remained engaging.

Observing his artistic progression, it becomes clear how deliberately he pursued this strategy. His techniques grew more visually arresting with each exhibition—evolving from heavy brushstrokes, textured impastos, and multilayered collages of the early 1960s to the increasingly sculptural mixed-media and assemblage works from the mid-1960s onward.

To illustrate this progression, below are close-ups from selected works exhibited between 1961 and 1969 (click to enlarge).

As this evolution shows, three-dimensionality emerged as Pignataro’s chosen device for engagement—a visual subterfuge inviting proximity while quietly leading the eye into the deeper, more demanding layers of his abstractions.

•••

A New Visual Language Emerges

Up until 1969, everyday objects were the primary means by which Roberto Pignataro infused three-dimensionality into his work. Sliced corks, staples, matches, sisal thread, bottle lids, punched tape, paper, and rubber bands frequently appeared in his assemblages, forming pronounced textures, raised grids, topographic surfaces, and protruding motifs.

Close-up of № 1012 (1967), Roberto Pignataro. Featuring cork slices and oil paint tube caps.

For his 1970 show, however, he sought a new approach. Determined to move beyond the familiar vocabulary of assemblage, Pignataro set out to explore three-dimensionality through compositional methods that had not been attempted before.

To this end, he returned to a technique he had quietly introduced in his 1968 show: the controlled application of small oil paint squeezes directly onto the canvas, producing scattered raised dots that added visual rhythm and a subtle tactile presence to the work.

This curious technique resurfaced in his subsequent 1969 exhibition at Galería Lirolay, appearing in two assemblages. In the first one (below, left), the dotted deposits lie loosely scattered across pale areas of the surface, particularly around the white impastos and bluish cork slices. In the second (below, right), the dots cluster more densely, forming intricate groupings across the red field.

Comparing the two pieces, it becomes clear that № 1168 marks a decisive shift in the technique. Here, the raised dots no longer sit quietly as supporting elements within a larger assemblage—they assert themselves as the foundation of a new visual logic. This is the moment when Pignataro turned what originated as a modest device into a full compositional strategy of its own, opening entirely new possibilities for oil paint as a medium.

Full view of artwork “№ 1168”

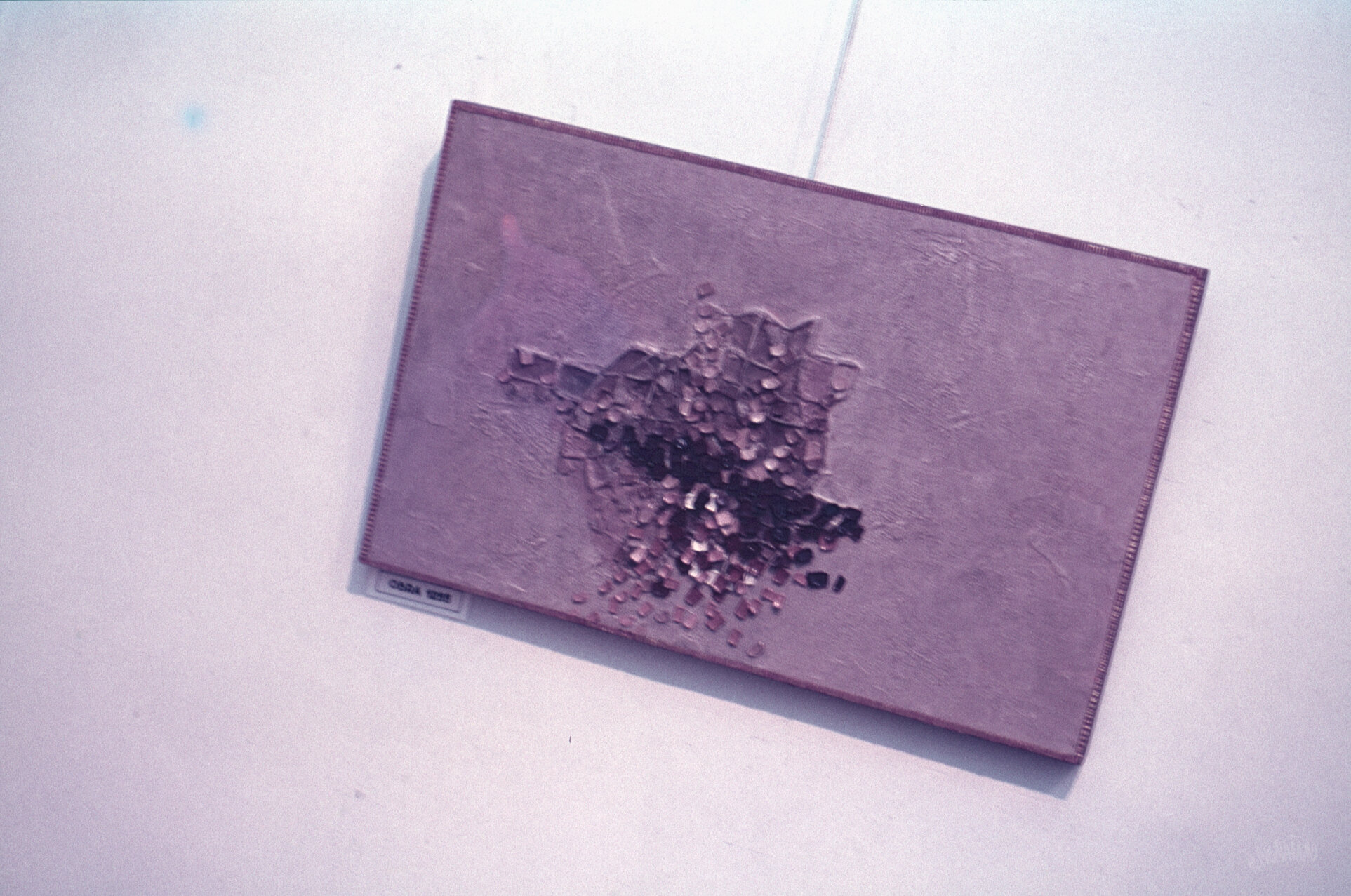

As he composed the works for his upcoming 1970 show, he expanded this technique to new extremes. No longer confined to a supporting role, the extruded paint bits now swept across entire surfaces—taking on diverse shapes such as circles, triangles, squares, ovals, even crescent moons—and forming intricate, multilayered structures.

The slideshow below shows the result: ten abstractions entirely developed in this new visual language.

•••

Observing these pieces up close, it’s hard to overstate how insane this technique really is. The artistic novelty alone is remarkable—but the technical gamble is borderline reckless. Given how notoriously difficult oil is to control at this level; you might spend an entire week shaping these structures only to watch it all collapse from a slip of the hand, a bad call, or simply because the composition didn’t evolve as you hoped. And there’s no undo button—a mistake at this stage means tearing it all down and starting over. Yet he pulled it off, and with a level of material detail and color nuance that defies what should be possible.

Close-up of "№ 1227" (1969), by Roberto Pignataro.

Close-up of "№ 1220" (1969), by Roberto Pignataro.

Like most artists, Roberto Pignataro’s path into modern art was inspired by earlier movements — Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, ancient Japanese art, etc. Although his work always carried a distinct identity, elements of these influences had remained visible up to this point.

What emerged in his 1970 show, however, was different. Existing art categories were no longer sufficient to fully describe what he unveiled. These ten abstractions stepped so far beyond recognizable precedents that, even today, trained and art-literate viewers struggle to articulate what stands before them.

Perhaps the most notable example of this came in the last week of September 1970, when art critic César Magrini stopped by Galería Lirolay to view the show. Let me now share the story.

•••

An Art Critic Enters the Room

César Magrini (1929–2012) — Argentine writer, journalist, and art critic.

With all the pieces now finished, Roberto Pignataro’s 1970 show was finally inaugurated on Monday, September 28 at Galería Lirolay.

He typically did not remain present during his exhibitions. Unlike many artists, Pignataro did not enjoy the limelight. Furthermore, he believed an artist’s presence could interfere with the viewer’s unmediated encounter with the work — an experience he wanted to unfold freely, without suggestion or influence.

This show was no exception. By the time a visitor stepped into the gallery, Pignataro was almost certainly at his desk at the Central Bank of Argentina, immersed in his daily number-crunching routines, far from the space where his abstractions silently hung.

One of those visitors was César Magrini — a leading Argentine writer, journalist, and art critic deeply involved in the country’s cultural scene of this period.

It was in this setting — a show in progress, with Pignataro absent by design — that Magrini walked into the gallery and encountered the new works for the first time.

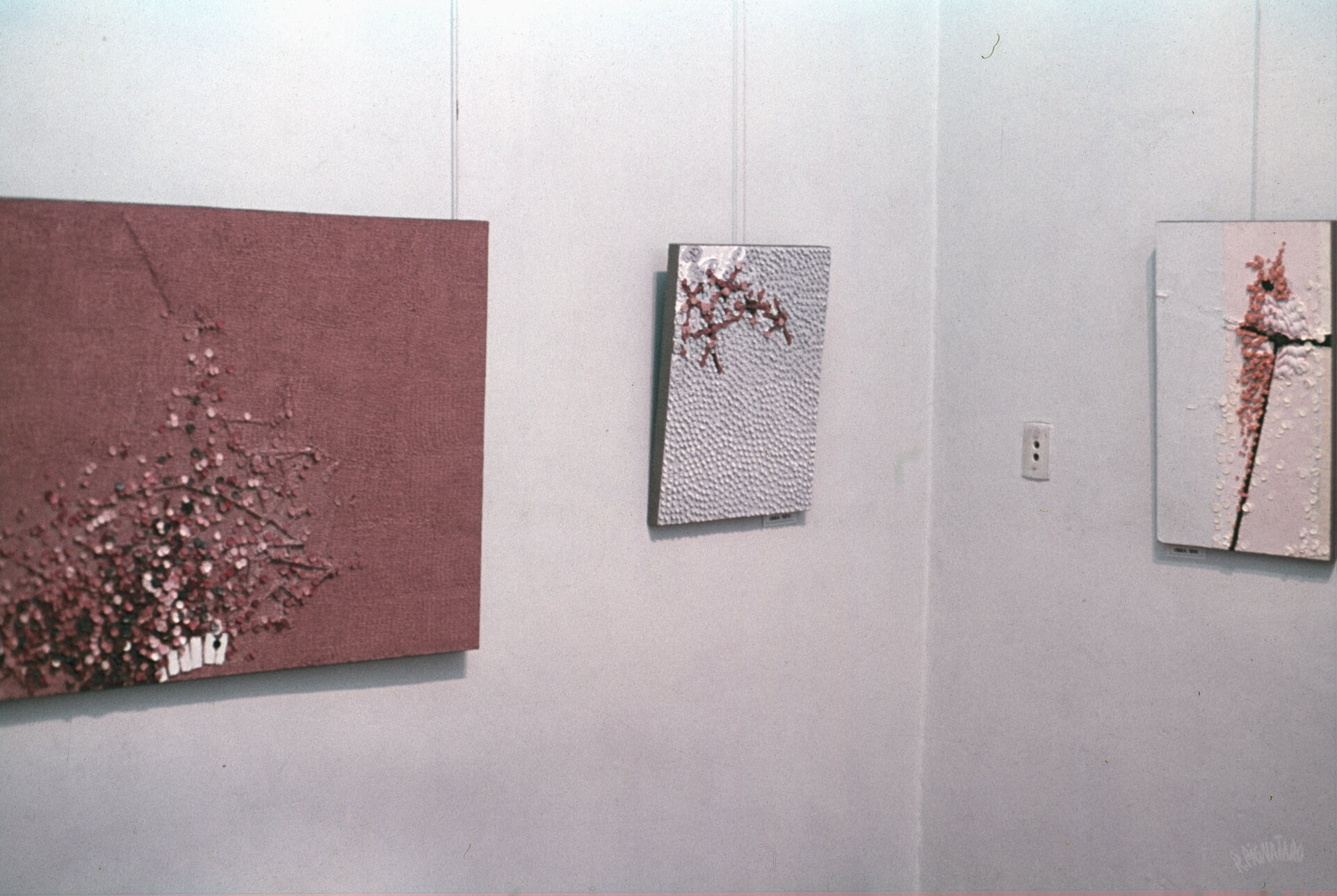

Interior view of Galería Lirolay, c. September 1970, during Pignataro’s exhibition.

Artwork visible in the back room is by Blanca Medda, another artist showing simultaneously at the gallery.

Pignataro maintained a warm relationship with Galería Lirolay’s owners, Mario and Paulette Fano. Though he avoided being present during opening hours, he often stopped by in the evenings to hear how the day had unfolded. Paulette, who usually managed the gallery floor, would recount who had visited, whether anyone notable had come through, and how viewers had responded.

That day, she told him that César Magrini had come in — and had spent more than thirty minutes moving slowly through the room, returning to certain works again and again. He said almost nothing; he simply looked stunned, absorbing the pieces in silence, occasionally taking notes, before eventually stepping back out onto the street.

César Magrini, “Aprendiz de Hechicero,”

El Cronista Comercial, no. 20.590, September 1970, “Galerías” section.

It was only the next day that his reaction found language when he published a review in El Cronista Comercial — one of Argentina’s leading newspapers — putting into words the impressions this show had left on him.

In the next section, I will walk through Magrini’s review, excerpt by excerpt, tracing how he responded to the work, what elements compelled his attention, and how his language engages with a visual vocabulary that had not yet found a place in the Argentine art landscape.

Before we jump into it, here is a full transcript of Magrini’s article, both in Spanish and English.

•••

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

I must confess, when I first read the title of Magrini’s article, “Aprendiz de Hechicero” — The Sorcerer’s Apprentice — I twisted myself into knots trying to understand the association he might have drawn between Goethe’s famous poem and Pignataro’s show. Eventually I realized it was less a literary reference than a it was playful metaphor — a wordplay he used to capture his enchantment with the exhibition.

With the title explained away, let’s now dive into the actual writings:

“At Lirolay, we’ve just seen a tightly arranged exhibition — small in physical space yet expansive in what it held — of works by Roberto Pignataro.

To define it is extremely difficult: like an illuminated child, he has chosen for his compositions the most unusual materials — fragments of glass in various colors; the purest and most pliable magic enclosed within a single chromatic range that nevertheless, by its very vitality, is capable of producing all tones; tiny pieces of (perhaps) ceramic, which he combines like fantastic fleurs-de-lis, like variegated and mysterious fruits — the reign of the finest charm, of the most total and contagious suggestion.”

What immediately stands out in this first excerpt is his struggle to describe what he was seeing. Also notable is his misidentification of the technique — he read the sculpted oil-paint forms as fragments of glass and ceramic. In a way, this misinterpretation works because it suits the poetic tone of his article, but it underscores just how unfamiliar this material language was at the time.

“Pignataro, who seems by nature elusive and withdrawn (the small card announcing the exhibition says simply, “Roberto Pignataro in recent paintings,” and I recall an excellent previous show of his), has now turned — with astonishing results — to mastering a material that in other hands would be foreign to painting and to art, and that can only approximately be defined as “assemblage.””

This passage is particularly important. While Magrini continues to grapple with how to classify the work, he also recognizes Pignataro as an artist working entirely on his own terms — in full command of his creative process and far removed form the shadow of the artistic influences he may have had in the past.

Interestingly, Magrini also notes Pignataro’s elusiveness, echoing what I discussed earlier about his deliberate absence. Unbeknownst to him, this observation reinforced Pignataro’s belief in maintaining distance between artist and viewer. In other words, had Pignataro been present when Magrini visited, the “magic” of his encounter with the artwork might have been diluted by conversation, explanations, or other interpretive cues.

“Of course, he does not stop there; but his character — which can be guessed or intuited from what’s on display, and in the fact that he has not titled his works, only mere numbers (a sign, this, of a sincere intellectual rigor, and one that also helps to situate him) — flourishes widely in his pictures. Yes, pictures — because they immediately awaken in the viewer sensations of the most refined beauty, and on a level of incorruptible honesty.”

Here, Magrini astutely reads Pignataro’s refusal to use descriptive titles not as avoidance but as discipline. By withholding language, he ensures that meaning arises from the encounter itself, rather than from the artist’s direction — a stance Magrini implicitly affirms in his own response.

Magrini then goes on to discuss each piece individually. These can be read in the transcripts linked above, but in essence his comments moves between close observation and poetic metaphor — naming colors and textures, then drifting into images of childhood, fairy tales, and hidden worlds. His response is sensorial rather than analytical, meeting the works through imagination and astonishment rather than technical classification — once again reinforcing the almost magical nature of his experience with the work.

“Someone deep and profoundly original, with a language of his own — lofty, poetic. Someone whose works one ought to see more often, because they rescue us from so much monotony, so much flatness, so much painful poverty as that which daily besieges us.”

For a critic who spent his days moving through exhibitions, Magrini’s closing remarks are quite revealing — as much a praise for this show as they are a scathing indictment of the broader Buenos Aires art scene of this period. He pulls no punches, casting Pignataro’s work as a rare moment of clarity amid the creative impoverishment he saw everywhere else.

To wrap up, it is worth noting that Magrini and Pignataro had not yet met in person before this article, even though Magrini had seen an earlier show, as he mentions. They would cross paths only briefly in later years. In other words, this review came from a place of genuine reaction — uncolored by personal familiarity or obligation.

•••