Artwork 440 by Roberto Pignataro (1958)

Music was a constant presence in Roberto Pignataro’s life. He grew up in the 1930s and 1940s during the golden age of tango, absorbing the rhythms and melodies that filled Buenos Aires cafés, dance halls, and radio broadcasts.

The great tango orchestras of the era—led by maestros such as Francisco Canaro, Julio De Caro, Juan D’Arienzo, and Aníbal Troilo—became the soundtrack of his youth, shaping his early musical sensibility and leaving impressions that would stay with him for life.

Beyond his passion for tango, he became particularly drawn to jazz, along with classical orchestral music, and African tribal drumming. Over time, he became a true melomaniac, cultivating eclectic tastes and maintaining a vast collection that spanned vinyl records, reel-to-reel tapes, and cassettes he recorded himself.

This article examines select instances in his career when the influence of music shaped his work—beginning with recognizable manifestations during his early figurative period, and later converging with abstraction to produce more subtle, yet uniquely expressive results.

•••

Ludwig van Beethoven (1953)

Perhaps the earliest reference to music in Pignataro’s art emerged in 1953, during his time at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Manuel Belgrano. That year, he created a drawing of Ludwig van Beethoven—a striking portrayal that not only captures his reverence for the legendary composer but also demonstrates an early interest in music as a force of expression.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven by Roberto Pignataro, 1953

Unfortunately, this drawing is the only surviving work from those early years in art school. Because of this gap, it wouldn’t be until the late 1950s that we see music resurface in his work.

•••

“Con la Trompeta” (1957)

“Con la Trompeta” by Roberto Pignataro, 1957

Notably, Pignataro’s next reference to music emerges in a public setting. It was in 1957, when he submitted a cubist-inspired painting titled Con la Trompeta to the LRA Radio Nacional art contest, an event that invited Argentine artists to explore music as a theme.

The work portrays a trumpet player rendered in a dynamic, monochromatic palette, evoking the improvisational energy and syncopation often associated with jazz.

At the time, Con la Trompeta was selected as one of the four winners and later published on the cover of the radio station’s magazine, marking Pignataro’s first participation in a public exhibition and an important early milestone in his career.

•••

Art School Work (1958-59)

Following Con la Trompeta, music remained a frequent theme in Pignataro’s art school work. Here is a group of paintings he created between 1958 and 1959, in which musicians and their instruments continue to take center stage.

It’s worth noting that these pieces weren’t created one after the other—they span a year, during which Pignataro explored many unrelated subjects in between. Therefore, it took me some time, careful sorting and observation to identify the musical thread.

When I first noticed the pattern, I couldn’t help wondering if all these musicians belonged to the same orchestra—as if he had deliberately scattered fragments of a single composition across different canvases, like pieces of a hidden puzzle. While there might be some truth to this theory, the more I looked, the clearer it became that he was drawing on a much wider constellation of musical references—from classical ensembles and folk traditions to jazz groups and more symbolic evocations—connecting the works not so much through a single performance, but through the broader idea of music itself.

Perhaps a more unifying thread can be found in his use of color—vibrant, contrasting and moody—which evokes theatrical context around the musicians. This positions Pignataro not merely as the painter but also as a member of the audience, as if each piece were a visual reflection of his experience viewing live concerts.

•••

Music as a Shaping Force

After 1959, Pignataro began moving away from figurative styles, shifting his focus toward abstraction. Yet musical references continued to surface in his work—perhaps more subtly and less frequently, but with no less intention or expressive power.

In the following sections, I’ll explore a selection of these compositions and reflect on their relationship to music.

Before diving in, however, it’s worth acknowledging the abstract nature of these pieces—meaning they can evoke different things to different people. Their visual language may not even point directly to music, at least not in any literal or obvious way. But that’s the beauty of abstraction: it doesn’t explain, it evokes. It opens a space where meaning is felt more than defined. And it’s in that spirit that I share my impressions—not as fixed interpretations, but as personal responses shaped by memory, emotion, and the connection I sense between these works and the idea of music.

“Untitled” (1960)

“Untitled”. Created in 1960 by Roberto Pignataro.

I still remember discovering this painting—not long after my father passed away. It was rolled up with a few others, tucked away in the back of a built-in closet, like a quiet souvenir from his art school days—never meant to be seen again.

It took me a couple of weeks—gently coaxing the curled paper back into shape—before I could fully take it in. And once I did, I was blown away. Not just by its striking colors and intense visual energy, but by the bold black motif at its center. To me, it instantly conjured the image of an orchestra conductor, frozen mid-gesture, drawing the music toward its crescendo. Within that frame, the red background quickly snapped into meaning—like a visualization of sound itself, stridently blasting forward at the conductor’s command.

In trying to understand my read on this piece, I think it traces back to how much Roberto Pignataro enjoyed orchestral music—and to my memories of him often tuning in on the radio or watching concerts and operas on TV.

•••

Artwork “264 CO” (1963)

First exhibited in 1964 at Galería Van Riel, the painting below has always caught my attention—especially for the way it evokes the visual impression of sound waves, like those displayed on an a vintage amplifier’s oscilloscope.

“264 CO” Created in 1963 by Roberto Pignataro

Although this piece is clearly rooted in abstract expressionism—a movement not primarily concerned with music—it nonetheless feels suffused with its presence. Not as a literal subject, but as an underlying force shaping a larger visual narrative—emerging as rhythm, pulsing energy, and a sustained sense of tension and release, ultimately giving the piece an unmistakable musical structure.

•••

Artwork “№1262” (1969)

As an avid tango listener, Pignataro was highly attuned to the emotional intensity and dynamic shifts of the genre. From the plaintive melancholy of a bandoneón solo to the surging crescendos of the full orchestra, tango music resonated deeply with him, and elements of this sensibility can be sensed in this assemblage from 1969:

Artwork “№1262”. Created in 1969 by Roberto Pignataro

The cluster of dots radiating upward from what appears to be a suggestion of piano keys—or perhaps a bandoneón in play—can be seen as a kind of explosive force, like sound momentarily taking shape in the air, or perhaps the bandoneón’s buttons erupting in motion as the melody peaks.

I personally see visual echoes of Quejas de bandoneón, the famous tango piece by Aníbal Troilo—one of Pignataro’s favorite composers. To me, it evokes that moment when the pianist leads the orchestra into an abrupt crescendo, masterfully transforming a quiet lament into an outpouring of raw emotion (see here).

•••

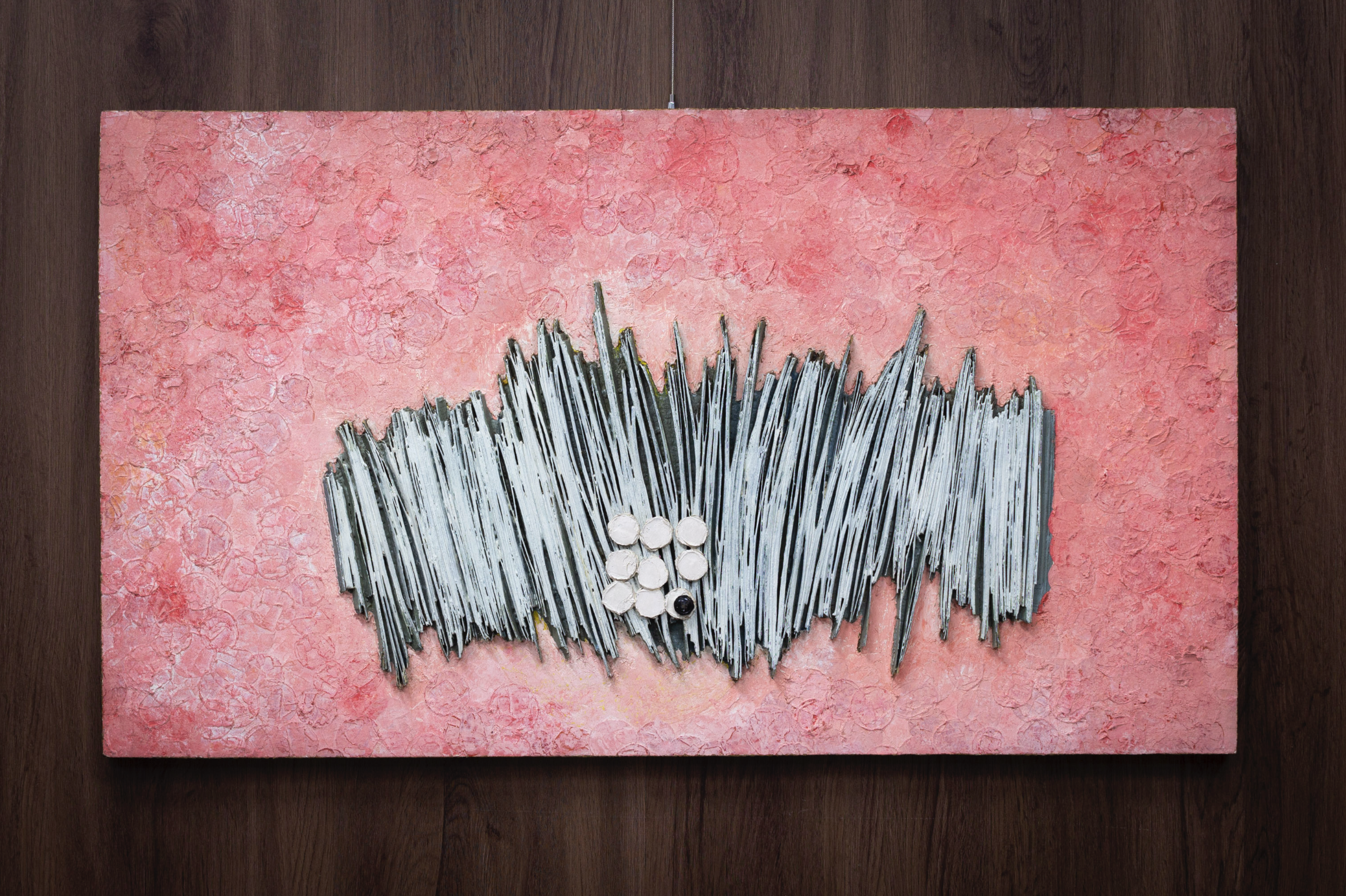

Artwork № 1031 (1967)

Much like the earlier work “264 C.O.,” this 1968 assemblage features a central motif that is highly evocative of the energy of sound, like a waveform frozen mid-vibration. The form itself is built from layered construction paper, giving the piece a striking three-dimensional presence that pushes the abstraction into real space.

Artwork № 1031. Created in 1967 by Roberto Pignataro

While the motif strongly suggests the shape of a bandoneón, it also conveys, just as vividly, the spontaneity of an improvised jazz riff—another genre Pignataro deeply admired. You can feel it in the way the layered paper juts and twists in unexpected directions, almost as if each piece is following its own rhythm, yet somehow all coming together in harmony.

Set against a vibrant pink background, the entire composition feels like a truly heartfelt tribute to the energy of music.

•••

The Arax Collection (1966)

Of all the abstract pieces I’ve reviewed so far, this collection is the only one with a concrete, documented connection to music. And it comes with an interesting backstory, which I’ll share below.

In 1966, Roberto Pignataro was invited by some Mr. Persichini of Philips Records to participate in an ambitious interdisciplinary project titled 14 con el Tango.

Conceived by the cultural impresario Ben Molar, the idea was to release a vinyl compilation of fourteen tangos, each pairing a renowned composer with a major Argentine writer—figures like Jorge Luis Borges, Leopoldo Marechal, and Ernesto Sabato among others.

But the project didn’t stop at music and literature. To visually anchor each piece, fourteen contemporary artists were selected to interpret the spirit of their assigned tango through original artwork, which would serve as the album’s graphic presentation, including notable painters such as Carlos Alonso, Raul Soldi, and Córdoba Iturburu.

The details of how Pignataro became involved remain unclear. What we do know is that he was asked to propose artwork for the project.

Altogether, he produced over sixty abstract collages for submission—a bold, experimental body of work that fused his signature style of abstraction with the playful, punchy aesthetics of 1960s graphic design. True to his vision, the pieces don’t represent music so much as embody its energy (the gallery above features sixteen selections from that collection).

It’s uncertain how many pieces he submitted—or which ones. The outcome remains just as opaque. While we know his work was ultimately not included, no explanation was ever documented. One plausible theory is that his collages—entirely nonfigurative and resistant to narrative—may have felt too abstract for a project that leaned heavily on cultural familiarity and visual storytelling. Still, without clear records, the real reason remains open to speculation.

Partial view of the 1966 “14 con el Tango” collection, showing nine of the fourteen original album covers—each featuring artwork by a different Argentine visual artist in response to an individual tango composition.

Whichever the case, this artwork collection didn’t go to waste. The pieces were exhibited to the public a year later at Galería Arax—hence the name of this collection—in a rotating format, with four works on view at a time, changing weekly.

•••

Conclusions

For anyone who knew Roberto Pignataro well, the sight of him meticulously cataloguing his music collection—or launching into an impassioned monologue about Django Reinhardt, or recounting detailed tales of Buenos Aires’ early tango orchestras—was a familiar one. He lived music intensely—not just as a listener, but as someone who studied its history and analyzed its structure, rhythms, and emotional architecture. It’s no surprise, then, that these sensibilities eventually found their way into his artwork.

With this in mind, I should make it clear that music was never the primary driving force behind Pignataro’s artistic career—rather, it was a constant companion, occasionally slipping onto the canvas in unexpected ways. That, ultimately, was the aim of this article: to shed light on this interesting aspect of his career that might otherwise have remained in obscurity.